|

by Leigh Montville

Sports Illustrated, Vol. 84 No. 22

THE MIDDLE-AGED man said he had two rubber rats stuffed in his crotch. He said he had two more rats stuffed in his armpits.

There were other rats, too, he said, hidden in other places on his body, but he declined to elaborate. Fair enough. "I have

enough rats," he said, "to do the job.

It was late in the afternoon on one of those 90° spring days in Miami that tell you summer has arrived in South Florida

and the next easy breath might not be drawn in these parts until sometime in late September. The man was standing across the

street from Miami Arena a few minutes before Game 3 of Game 4 or maybe even Game 6 of the Florida Panthers' Eastern Conference

finals series against the Pittsburgh Penguins. It's hard to say which game because-looking now at the dizzying swirl of celebration

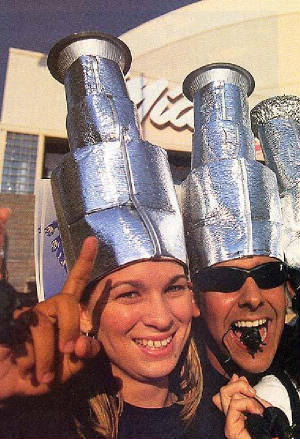

that has engulfed the Miami area during the NHL playoffs-everything has become a blur. The man was wearing a sponge-rubber

hat shaped like a wedge of cheese. Heads and tails from rubber rats stuck out from the sponge-rubber wedge of cheese. The

rats' eyes blinked electronically. The eyes were red.

Miami! Rats! Hockey! The improbable Panthers were on their joyride to the Stanley Cup finals against the almost-as-improbable

Colorado Avalanche and…and what?

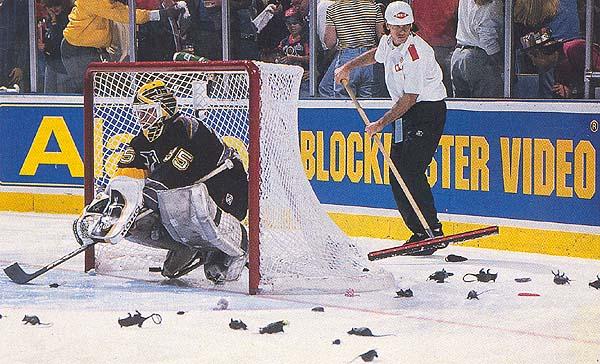

Rubber and plastic rats were being thrown from the rafters of Miami Arena to celebrate every Florida goal. The shower

of synthetic rats had grown heavier with each playoff round and by last week had turned into a veritable Biblical plague.

Hockey was being discussed in Spanish at the sidewalk cafes in South Beach. Singers at the Howl at the Moon Saloon club in

Coconut Grove were being drowned out by the chant "Let's Go, Panthers!"

"You have to sneak the rats into the building," the man, Dan Platt, a telephone worker from Hollywood

Beach, Fla., said. "You can't just walk into the arena carrying a rat, you know. They check you. Security. They make men take

off their hats. They open women's pocketbooks. If you get caught, you have to check the rats at Guest Relations. That's if

you get caught."

"The other day we tried to figure out how much people had paid for all the rats that have been thrown on the ice this

year," Dean Jordan, the Panthers' vice president of business operations, said after Florida, a third-year

expansion team, completed its run to the finals with a 3-1 road win over the favored Pittsburgh Penguins last Saturday night.

"We know roughly how many rats have been thrown, and we have a pretty good idea how much they cost. The estimate we made was

$55,000. Think about that-$55,000 worth of rats.”

From one rat intruder in the locker room, killed by Florida winger Scott Mellanby's stick moments before

the Panthers took the ice for their home opener on Oct. 8, to $55,000 worth of synthetic rats being heaved onto the ice to

celebrate a march to the Stanley Cup finals: Has so strange a good-luck ritual-Mellanby's deadly stick scored two goals that

first night, and the story of his exploits in the dressing room and on the ice begat one rat, two rats, now thousands of rats-ever

grown so large? Has there ever been a more extreme contrast of cold-weather sport and warm-weather city? Sled-dog racing in

Cairo! Hockey in Miami!

"It's all happened so fast, I don't think any of us knows what's hit us," said Jordan.

"The franchise was awarded in December of 1992, but we didn't really set up shop, have an office and everything, until

June of 1993. Our first season started in September of 1993. None of the business people, myself included, knew anything about

hockey. I remember a meeting that June, we had this big pad and a pencil and we were telling our people, 'O.K, we're in the

Atlantic Division, and these are the names of the other teams in our division.' That's how basic we had to be."

A team that three years ago didn't even know what its fan base would be-one mistaken thought early on was that vacationers

from the North would be among the primary ticket buyers-has suddenly discovered in the playoffs that the base reaches everywhere

and includes everyone. From the Keys to Palm Beach and beyond, a love affair has developed in a hurry.

As the Panthers' recycled journeymen and teenage draft choices, backed by All-Star goalie John Vanbiesbrouck,

rolled through the Boston Bruins in five games, the Philadelphia Flyers in six and the Penguins in seven, the mania grew.

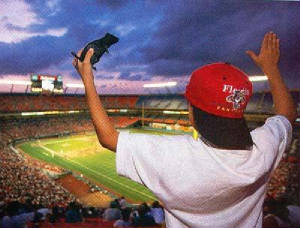

Supermarkets in the Miami area are selling special rat cakes--cupcakes with rats drawn in frosting on the top. Players

are being given standing ovations when they walk into bagel shops for breakfast. At Joe Robbie Stadium on

Saturday night, the Florida Marlins showed Game 7 of the Panthers-Penguins series on the mega screen between innings. Miami

Arena public address announcer John DeMott was on hand to call the Florida goals with his familiar cry of

"Pannnnnnthers!" After each of the three Florida tallies, the ballpark rang with shouts of "Goal!"

"It's all happened overnight," Miami Herald columnist Dan Le Batard said last weekend.

"If any columnist in South Florida tells you that before April he knew the color of the blue line, he'd be lying. Now

we're all writing about back checking schemes in the neutral zone."

Le Batard points at his own family as evidence of the burgeoning interest. His parents were born and raised in Cuba.

Until recently neither had ever been to a hockey game.

Neither knew anything about the sport.

Le Batard's father, Gonzalo, asked Dan if the puck was "made of steel." His mother, Lourdes, watched a Florida - Philadelphia

playoff game thinking for half of it that the Flyers were the Panthers because they had the letter P on their jerseys. Game

6 against Pittsburgh, a 4-3 Florida win, was the second game his parents attended.

"My father was crying at the end," Dan says. "He's not an emotional man. I think I can count on one hand the number of

times I've ever seen him cry. This was one of them."

The fans have been drawn in by the magic of an underdog fighting for a championship. Never mind that many don't know-or

care about such technicalities as off sides and icing.

Score a goal.

Throw a rat.

What's hard about that?

Approximately 40 arena attendants, dressed in Orkin Exterminating uniforms in a fine show of instant commercialism, run

onto the ice with large buckets to clean up the rodents as the opposing goalie huddles inside his net for safety.

"The number of rats gets bigger and bigger," says Danny Reiter, a member of the Orkin sponsored cleanup

crew. "After the first goal in the first home game of the series against Pittsburgh, we filled two barrels for the first time

this season. There must have been, what, 3,000.rats on the ice?" "There are the rubber ones, the plastic ones and these kind

of furry ones that some people throw," says Reiter's sister Jodi, who also works on the crew. "The furry ones are the ones

you don't really want to touch. Do you know what I mean? They're too real. Creepy. You get hit off the head a lot. It's

like people are aiming for you. I got hit off the head the other night with a computer mouse."

The No.1 question for Panthers public relations director Greg Bouris is "What happens to all those rats

after they're taken from the ice?" His answer: "They're destroyed humanely."

DeMott delivers a monotone Miranda-like warning over the P.A. system before each game, telling fans they should not be

throwing "anything onto the ice at any time," but team owner Wayne Huizenga wears a white rat pin on his

suit coat. His wife, Marti, throws rats.

His son Wayne Jr. also throws rats.

"He throws out a rat that has a string attached to it," one of the Orkin workers says of Wayne Jr. "You go to pick up

the rat and he pulls the string. Scares you to death."

"How old is he?" another worker asks. "About 10 years old?"

"No, he must be 30, maybe 35."

The Panthers' success is best illustrated by the dark stitches and purple lines across the faces of the players. A black

eye for Mellanby. Three stitches and a broken nose for Tom Fitzgerald. Ten stitches for Stu Barnes.

Three missing teeth for Radek Dvorak. Aside from Vanbiesbrouck, this is a no-star, low-budget operation-which

is part of its charm. Work harder. Work longer. Dive. Fight. Survive.

Two months ago the faces wouldn't have been recognized five steps away from the team's practice rink in Pompano Beach.

Now a disc jockey does his show from the Miami Arena parking lot. A woman brings a special blend of five grapefruit juices

for the players, Panther Punch. A man brings his homemade banana bread. The unknown players are becoming known.

"This team is still in kind of an embryonic stage in a lot of ways," says Florida president Bill Torrey,

the architect of the New York Islanders' four Stanley Cup championships from 1980 to '83. "The Islanders were much more developed.

We have no big playmaker on this team. We have no 50-goal scorer. What we do have is great team speed, four lines that all

play our system and two forecheckers who go deep. With [6' 2", 210-pound] Eddie Jovanovski and [6' 1", 210-pound]

Rhett Warrener, we added size and strength at the blue line. And we work. This isn't a team that will just

go away."

What's next? Can this team finish off perhaps the greatest surprise in NHL history?

Can it handle this final challenge from Patrick Roy and the Avalanche, yet another team that appears

more talented?

Will the Panthers be the first hockey team to have a mambo or a tango or a cha-cha-cha written in honor of its accomplishments?

Will fans in Golden Age neighborhoods turn up their hearing aids and slow down their pacemakers for the finals? Has Fidel

Castro been watching and enjoying? Is the puck truly made of steel? Or just the men?

What?

"They call me Ratman," Platt says in his cheese hat that's filled with rats. "I'll be there."

"Are you the only Ratman?" he is asked. "Or are there other Ratmen, too?"

"There's a guy, wears a whole rat suit," Platt says. "You'll see him. I'm told he's a psychiatrist in the real world.”

|